The US president is not shy when it comes to praising autocratic regimes – good news for Hanoi, which is in the midst of a crackdown on anyone critical of its one-party state

Logan Connor, South China Morning Post, September 16, 2017

When US President Donald Trump met Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc in May, he sent a clear message: by patting the backs of authoritarian leaders, the US is complicit in Vietnam’s rights abuses.

Trump is no stranger to brushing shoulders with autocratic leaders. Allegations of cosying up to Russian President Vladimir Putin aside, he has praised Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, Egyptian leader Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

But Trump extending hands to Vietnam’s leader is perhaps unique given the two countries’ past animosity, and particularly since Hanoi’s crackdown on opposition voices, seen by many as its toughest in years.

A girl walks past a poster promoting Vietnam’s 14th National Assembly election in Hanoi last year. The ruling party has launched a crackdown on dissenting voices as the US has relaxed its push for improved human rights in the country. Photo: Reuters

Vietnam’s leaders – some of the most authoritarian in Southeast Asia – are determined to silence all forms of dissent that cause people to question the one-party state.

Last month, President Tran Dai Quang called for tougher internet controls on such voices and to “prevent news sites and blogs with bad and dangerous content”. Two weeks ago, authorities in Thai Binh province arrested a member of the online advocacy group, the Brotherhood for Democracy, for “subversion” in relation to his involvement in a land dispute.

The case highlighted Vietnam’s intolerance for such dissent and the political elite have shown they will cling to power by any means – harassing activists and bloggers, extracting confessions through intimidation, physical assault and imprisonment are often reported. So far this year, Vietnamese authorities have reportedly arrested 15 people for anti-state actions.

Vietnam President Tran Dai Quang is sworn last year. Photo: AFP

Vietnam President Tran Dai Quang is sworn last year. Photo: AFP

“By inviting Vietnam’s Prime Minister to the White House and then failing to raise any human rights issues, President Trump basically gave Hanoi the green light to initiate a renewed crackdown on rights activists,” said Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division. “Trump’s change in Vietnam policy amounted to throwing out the window the human rights concerns of the Obama administration, which had been one of Vietnam’s strongest critics.”

Robertson said he was not surprised to see Vietnam taking advantage of Trump’s apathy – and lack of US criticism – to ramp up its crackdown and hit prominent dissidents with a slew of long prison sentences.

“It looks like Vietnam is taking advantage of this current situation to try and set the human rights situation back to an earlier, more repressive past.”

US President Barack Obama gestures at Vietnam’s President Tran Dai Quang in Hanoi. The former US leader was more critical of the Southeast Asian nation’s human rights abuses, than the current US President Donald Trump. Photo: Reuters

US President Barack Obama gestures at Vietnam’s President Tran Dai Quang in Hanoi. The former US leader was more critical of the Southeast Asian nation’s human rights abuses, than the current US President Donald Trump. Photo: Reuters

But alleviating US pressure on Vietnam did not start with Trump. Though the Obama administration was known for pushing governments to improve their human rights situations, the former US leader last year lifted a long-standing arms embargo on Vietnam, which critics warned could remove incentives for the Southeast Asian nation to improve its human rights situation.

[TRUMP’S] PRIMARY INTEREST IS IN STRIKING TRADE DEALS WHICH ARE MORE BENEFICIAL TO THE US WITH FOREIGN PARTNERS

But under the Trump administration, Vietnam – and many other authoritarian states – have even less to worry about in terms of US wrist-slapping. The US president has not been shy in his praise of many hardline leaders around the world and has often touted a foreign policy that seeks to move away from the liberal, human rights-focused agenda of past presidents. Washington’s retreat from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which included rules aimed at promoting worker’s rights, left Vietnam with even fewer reasons to worry about international opinion.

Oliver Turner, an international relations lecturer from the University of Edinburgh, said a fundamental aspect of Trump’s administration was its tunnel vision.

“[Trump’s] primary interest is in striking trade deals which are more beneficial to the US with foreign partners, and it won’t be a surprise to see his administration negotiate these deals in the absence of concern for their records on human rights,” he said.

Turner said China’s growing presence and influence in Southeast Asia was also an critical factor, as Beijing surfaces as an attractive alternative to the US by offering funding without the human rights-oriented conditions that often came with US aid. But Vietnam and China have historical animosity, leaving Vietnam as one of Washington’s few remaining allies in the region.

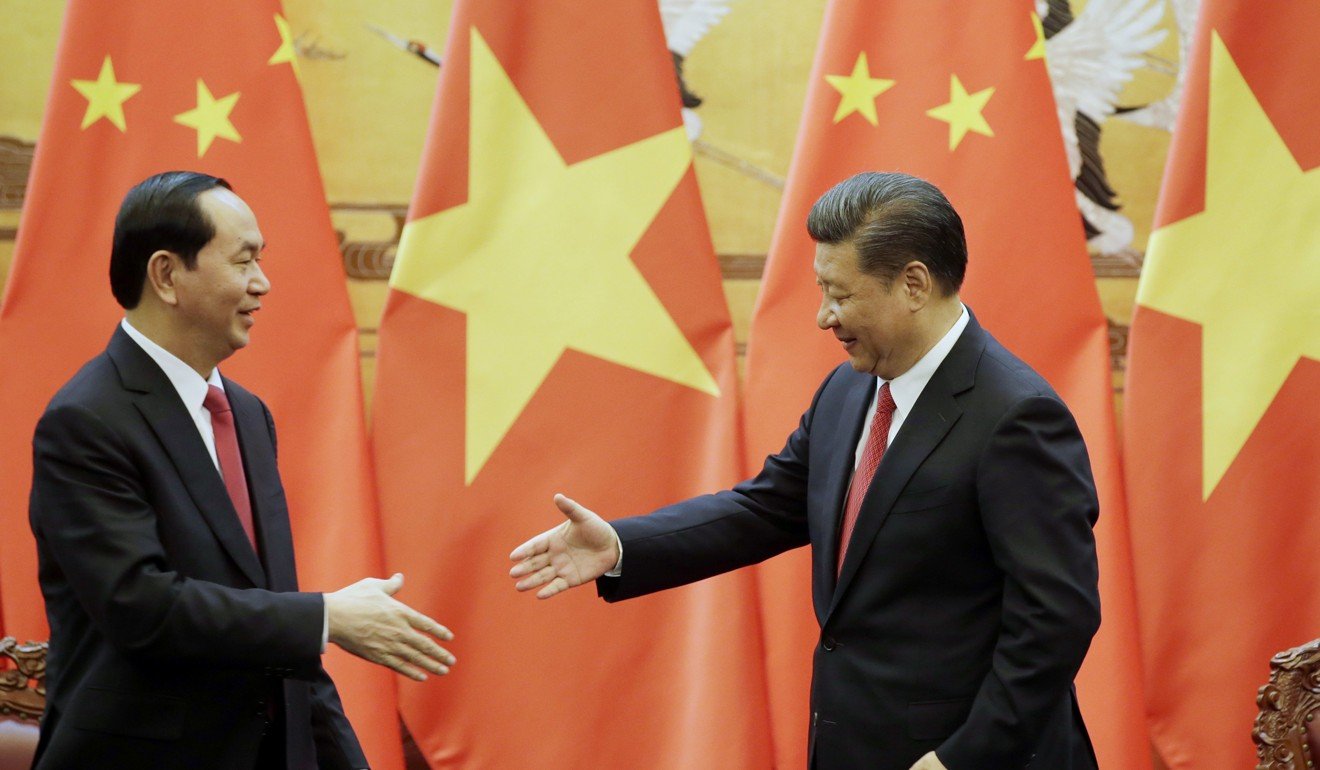

Vietnam’s President Tran Dai Quang with Chinese President Xi Jinping. Photo: EPA

Vietnam’s President Tran Dai Quang with Chinese President Xi Jinping. Photo: EPA

“I also think that with the Philippines, and to a lesser extent Thailand in particular, shifting their diplomatic allegiances towards China, relations with Vietnam will probably become more of a priority for Washington, making a future appeasement of human rights abuses more likely,” he said.

Despite having its own history of rights abuses in Southeast Asia – including an illegal war in Laos, wanton bombing in Vietnam and Cambodia and the backing of a genocidal regime in Indonesia – the US can still institute positive change in the region. Capable of applying concerted pressure on human rights issues, most dictators have to at least sit up and appear to listen to the US, Robertson said.

But such a prospect – US influence as a force for good in the region – may be no more than a pipe dream.

“The US has a role to play in curbing human rights abuses in Vietnam, most prominently through economic diplomacy and tying trade to the issue of human rights … this seems unlikely over the next four years,” Turner said.

“Washington could also rally like-minded allies in Asean [The Association of Southeast Asian Nations] to exert pressure on Vietnam, but Trump’s unilateralist approach to global affairs will likely have little time for, or faith in, such institutions.”

As long as Trump is in office – and is focused on threats like a nuclear-armed North Korea and domestic politics – residents of Southeast Asia may have to rely on themselves to promote free speech and other freedoms.

“Trump’s supporters will not measure his success in terms of upholding human rights, and Trump knows that, so it isn’t a priority for him,” Turner said.

“I think on the issue of human rights, it will increasingly be up to the Asean community to police itself.”

Height Insoles: Hi, I do believe this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon …

http://fishinglovers.net: Appreciate you sharing, great post.Thanks Again. Keep writi…

Achilles Pain causes: Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this site, as i w…

September 17, 2017

VIETNAM’S CRACKING DOWN ON DISSENT … SO WHY TRUMP’S PAT ON BACK?

by Nhan Quyen • [Human Rights]

The US president is not shy when it comes to praising autocratic regimes – good news for Hanoi, which is in the midst of a crackdown on anyone critical of its one-party state

Logan Connor, South China Morning Post, September 16, 2017

When US President Donald Trump met Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc in May, he sent a clear message: by patting the backs of authoritarian leaders, the US is complicit in Vietnam’s rights abuses.

Trump is no stranger to brushing shoulders with autocratic leaders. Allegations of cosying up to Russian President Vladimir Putin aside, he has praised Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, Egyptian leader Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

But Trump extending hands to Vietnam’s leader is perhaps unique given the two countries’ past animosity, and particularly since Hanoi’s crackdown on opposition voices, seen by many as its toughest in years.

A girl walks past a poster promoting Vietnam’s 14th National Assembly election in Hanoi last year. The ruling party has launched a crackdown on dissenting voices as the US has relaxed its push for improved human rights in the country. Photo: Reuters

Vietnam’s leaders – some of the most authoritarian in Southeast Asia – are determined to silence all forms of dissent that cause people to question the one-party state.

Last month, President Tran Dai Quang called for tougher internet controls on such voices and to “prevent news sites and blogs with bad and dangerous content”. Two weeks ago, authorities in Thai Binh province arrested a member of the online advocacy group, the Brotherhood for Democracy, for “subversion” in relation to his involvement in a land dispute.

The case highlighted Vietnam’s intolerance for such dissent and the political elite have shown they will cling to power by any means – harassing activists and bloggers, extracting confessions through intimidation, physical assault and imprisonment are often reported. So far this year, Vietnamese authorities have reportedly arrested 15 people for anti-state actions.

Vietnam voices second protest over China drills in disputed seas

“By inviting Vietnam’s Prime Minister to the White House and then failing to raise any human rights issues, President Trump basically gave Hanoi the green light to initiate a renewed crackdown on rights activists,” said Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division. “Trump’s change in Vietnam policy amounted to throwing out the window the human rights concerns of the Obama administration, which had been one of Vietnam’s strongest critics.”

Robertson said he was not surprised to see Vietnam taking advantage of Trump’s apathy – and lack of US criticism – to ramp up its crackdown and hit prominent dissidents with a slew of long prison sentences.

“It looks like Vietnam is taking advantage of this current situation to try and set the human rights situation back to an earlier, more repressive past.”

But alleviating US pressure on Vietnam did not start with Trump. Though the Obama administration was known for pushing governments to improve their human rights situations, the former US leader last year lifted a long-standing arms embargo on Vietnam, which critics warned could remove incentives for the Southeast Asian nation to improve its human rights situation.

But under the Trump administration, Vietnam – and many other authoritarian states – have even less to worry about in terms of US wrist-slapping. The US president has not been shy in his praise of many hardline leaders around the world and has often touted a foreign policy that seeks to move away from the liberal, human rights-focused agenda of past presidents. Washington’s retreat from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which included rules aimed at promoting worker’s rights, left Vietnam with even fewer reasons to worry about international opinion.

Oliver Turner, an international relations lecturer from the University of Edinburgh, said a fundamental aspect of Trump’s administration was its tunnel vision.

“[Trump’s] primary interest is in striking trade deals which are more beneficial to the US with foreign partners, and it won’t be a surprise to see his administration negotiate these deals in the absence of concern for their records on human rights,” he said.

Turner said China’s growing presence and influence in Southeast Asia was also an critical factor, as Beijing surfaces as an attractive alternative to the US by offering funding without the human rights-oriented conditions that often came with US aid. But Vietnam and China have historical animosity, leaving Vietnam as one of Washington’s few remaining allies in the region.

How Vietnamese millennials are broadening their horizons

“I also think that with the Philippines, and to a lesser extent Thailand in particular, shifting their diplomatic allegiances towards China, relations with Vietnam will probably become more of a priority for Washington, making a future appeasement of human rights abuses more likely,” he said.

Despite having its own history of rights abuses in Southeast Asia – including an illegal war in Laos, wanton bombing in Vietnam and Cambodia and the backing of a genocidal regime in Indonesia – the US can still institute positive change in the region. Capable of applying concerted pressure on human rights issues, most dictators have to at least sit up and appear to listen to the US, Robertson said.

But such a prospect – US influence as a force for good in the region – may be no more than a pipe dream.

“The US has a role to play in curbing human rights abuses in Vietnam, most prominently through economic diplomacy and tying trade to the issue of human rights … this seems unlikely over the next four years,” Turner said.

“Washington could also rally like-minded allies in Asean [The Association of Southeast Asian Nations] to exert pressure on Vietnam, but Trump’s unilateralist approach to global affairs will likely have little time for, or faith in, such institutions.”

As long as Trump is in office – and is focused on threats like a nuclear-armed North Korea and domestic politics – residents of Southeast Asia may have to rely on themselves to promote free speech and other freedoms.

“Trump’s supporters will not measure his success in terms of upholding human rights, and Trump knows that, so it isn’t a priority for him,” Turner said.

“I think on the issue of human rights, it will increasingly be up to the Asean community to police itself.”