Upland Vietnam has witnessed a remarkable religious transformation within one marginalized ethnic minority in the past three decades. Since the 1980s, where Protestant Christianity was virtually unheard of in Vietnam’s northern highlands, an estimated 300,000 out of the 1 million ethnic Hmong in Vietnam are now Christians. Over time, the social, economic, and political impacts of religious change – from persecution and migration to lifestyle changes and new gender relations – are becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

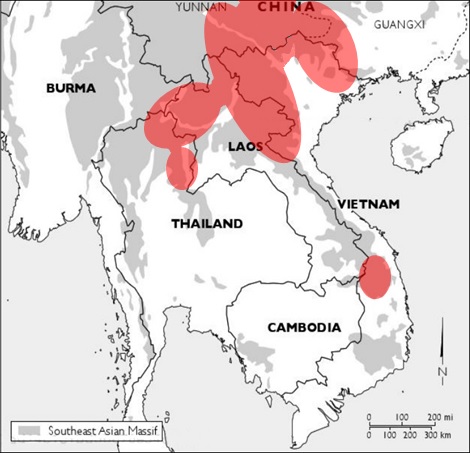

Today there are roughly 4 million Hmong speakers spread across the borderlands of China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand, plus significant diasporas in the United States and Australia. Their shared ethnic identity is built around speaking mutually intelligible languages and sharing the same clan surnames.

A map of Hmong-inhabited areas of Southeast Asia. Adapted from Jodi L. Weinstein’s Empire and Identity in Guizhou: Local Resistance to Qing Expansion, pp. vx © 2013. Reprinted with permission of the University of Washington Press

Somewhat akin to the Kurds of the Middle East, the Hmong are split into significant but marginalized national minorities. During the Cold War, the Hmong found themselves on both sides of the conflict between communist and American forces, with the infamous anti-communist general Vang Pao being funded by the CIA in Laos.

Surprisingly, no foreign missionaries were physically present in Vietnam’s highlands when Christianity started to spread in the late 1980s. Instead, villagers stumbled across a Hmong-language evangelistic radio program broadcast from Manila. Thrilled by hearing their own language on air, Hmong listeners told neighbors and relatives to tune in as the message spread like wildfire.

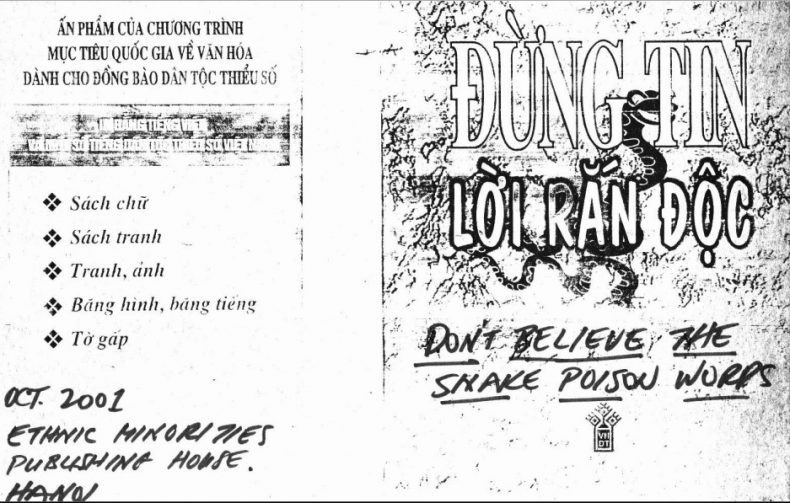

Vietnamese authorities reacted to Hmong Christian growth by denying its existence, publishing anti-Christian propaganda, and restricting religious freedom. With its history of struggle against Western imperialism, the government accused “hostile external forces” of promoting Christianity to undermine the people’s faith in Communism and trigger social unrest along the strategically important Sino-Vietnamese borderlands.

Book cover entitled Don’t Believe the Snake Poison Words (referring to Christian teaching) published in Hanoi in 2001.

Human rights watchdogs report of converts being intimidated, arrested, fined, beaten, having property confiscated, and being forced to renounce their faith by local authorities. Many Hmong fled the persecution to Laos, Thailand, and other parts of Vietnam to seek a better life.

State religious repression has eased in recent years, although it is still very difficult for new churches to gain official recognition. Significant religious discrimination remains as Christians are denied university scholarships or access to civil service positions, often the only way of securing a regular income in rural areas.

The Hmong are at the bottom of Vietnam’s ethnic hierarchy, with the highest poverty levels and lowest education levels. Due to their isolated location, the Hmong have not benefited from Vietnam’s economic growth; local state-led development initiatives frequently achieve disappointing results due to ethnic prejudice and cultural misunderstandings.

However, some Hmong Christians are now able to access new sources of funding, information, and power through religious networks. For example, various Bible schools in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City allow ethnic minority students to study and live there for minimal fees.

Hmong students attending a church meeting in Hanoi. Image by Seb Rumsby.

Hmong students learn much more than theology as they are exposed to an urban environment with new ways of thinking and earning a living, which they bring back to their villages after graduating. Church leaders also network with foreign missionaries and organizations at Christian conferences, some of whom are eager to fund church buildings or poverty relief initiatives.

42-year-old Ban became the default church leader of his village when he was the first person to convert back in 1992; at present, around three-quarters of the village are Christian. After studying theology in China and Hanoi for many years, Ban has developed strong external networks and wields more influence than the officially designated village elder, due to his spiritual authority.

Over the past five years, Ban persuaded his fellow villagers to embark on some substantial collective endeavors that have transformed his village from an impoverished backwater to a thriving tourist destination: building five kilometers of concrete road down to the main road, establishing a weekly market from scratch, and taking responsibility for clearing litter from the land.

Every Saturday, there is a church meeting in which villagers discuss the best ways to grow cash crops or raise livestock, as well as ensuring discipline in collective tasks being welcoming to tourists. Despite his extensive travels and connections, Ban says all his inspiration came from the Bible.

Pastor Ban (in the suit) with his village congregation. Image by Seb Rumsby.

Even formerly hostile government cadres acknowledge some potentially positive aspects of Hmong Christianity. For example, upon conversion Christians are strongly encouraged to quit drinking alcohol and smoking completely.

Since domestic violence is strongly associated with intoxication, Hmong women see Christianity as a path to empowerment and usually convert first, persuading their husbands to follow them. Although pastors are overwhelmingly men, women comprise the majority of congregations and lead in various activities of the church life.

On the other hand, alcohol consumption is traditionally an important form of male bonding, so refusing to do this has caused conflict between Hmong Christians and non-Christians. Families and communities have been torn apart as both sides harbor bitterness and misunderstanding towards each other, fueled by state denunciations of religious activity.

The qeej instrument (right) is an iconic cultural symbol, but is unpopular among Hmong Christians. Image by Seb Rumsby.

Another concern is that Hmong Christians often reject traditional religious rituals and ceremonies. Even traditional musical instruments like the qeej are treated with suspicion by Christians for their association with traditional funeral ceremonies, and are no longer taught to the next generation.

Many Hmong shamans and non-Christians fear that their culture is being lost. Government officials also worry, because ethnic tourism in the highlands is being promoted by putting these cultures and customs on show. Hmong Christians object to this accusation. Through studying the Hmong Bible, they claim to be preserving their language and script, a crucial aspect of culture that is no longer taught in schools.

In closing, pastors like Ban claim Christianity to be an alternative route to development for the Hmong despite government opposition, but this is contested. These issues are likely to become more and more visible as Christianity continues to grow among the Hmong and the other ethnic groups of Vietnam.

Seb Rumsby is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Warwick.

Height Insoles: Hi, I do believe this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon …

http://fishinglovers.net: Appreciate you sharing, great post.Thanks Again. Keep writi…

Achilles Pain causes: Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this site, as i w…

November 14, 2017

Vietnam Wrestles With Christianity

by Nhan Quyen • [Human Rights]

Why hundreds of thousands of ethnic Hmong have converted to Christianity in Vietnam over the past 30 years.

Upland Vietnam has witnessed a remarkable religious transformation within one marginalized ethnic minority in the past three decades. Since the 1980s, where Protestant Christianity was virtually unheard of in Vietnam’s northern highlands, an estimated 300,000 out of the 1 million ethnic Hmong in Vietnam are now Christians. Over time, the social, economic, and political impacts of religious change – from persecution and migration to lifestyle changes and new gender relations – are becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

Today there are roughly 4 million Hmong speakers spread across the borderlands of China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand, plus significant diasporas in the United States and Australia. Their shared ethnic identity is built around speaking mutually intelligible languages and sharing the same clan surnames.

A map of Hmong-inhabited areas of Southeast Asia. Adapted from Jodi L. Weinstein’s Empire and Identity in Guizhou: Local Resistance to Qing Expansion, pp. vx © 2013. Reprinted with permission of the University of Washington Press

Somewhat akin to the Kurds of the Middle East, the Hmong are split into significant but marginalized national minorities. During the Cold War, the Hmong found themselves on both sides of the conflict between communist and American forces, with the infamous anti-communist general Vang Pao being funded by the CIA in Laos.

Surprisingly, no foreign missionaries were physically present in Vietnam’s highlands when Christianity started to spread in the late 1980s. Instead, villagers stumbled across a Hmong-language evangelistic radio program broadcast from Manila. Thrilled by hearing their own language on air, Hmong listeners told neighbors and relatives to tune in as the message spread like wildfire.

Vietnamese authorities reacted to Hmong Christian growth by denying its existence, publishing anti-Christian propaganda, and restricting religious freedom. With its history of struggle against Western imperialism, the government accused “hostile external forces” of promoting Christianity to undermine the people’s faith in Communism and trigger social unrest along the strategically important Sino-Vietnamese borderlands.

Book cover entitled Don’t Believe the Snake Poison Words (referring to Christian teaching) published in Hanoi in 2001.

Human rights watchdogs report of converts being intimidated, arrested, fined, beaten, having property confiscated, and being forced to renounce their faith by local authorities. Many Hmong fled the persecution to Laos, Thailand, and other parts of Vietnam to seek a better life.

State religious repression has eased in recent years, although it is still very difficult for new churches to gain official recognition. Significant religious discrimination remains as Christians are denied university scholarships or access to civil service positions, often the only way of securing a regular income in rural areas.

The Hmong are at the bottom of Vietnam’s ethnic hierarchy, with the highest poverty levels and lowest education levels. Due to their isolated location, the Hmong have not benefited from Vietnam’s economic growth; local state-led development initiatives frequently achieve disappointing results due to ethnic prejudice and cultural misunderstandings.

However, some Hmong Christians are now able to access new sources of funding, information, and power through religious networks. For example, various Bible schools in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City allow ethnic minority students to study and live there for minimal fees.

Hmong students attending a church meeting in Hanoi. Image by Seb Rumsby.

Hmong students learn much more than theology as they are exposed to an urban environment with new ways of thinking and earning a living, which they bring back to their villages after graduating. Church leaders also network with foreign missionaries and organizations at Christian conferences, some of whom are eager to fund church buildings or poverty relief initiatives.

42-year-old Ban became the default church leader of his village when he was the first person to convert back in 1992; at present, around three-quarters of the village are Christian. After studying theology in China and Hanoi for many years, Ban has developed strong external networks and wields more influence than the officially designated village elder, due to his spiritual authority.

Over the past five years, Ban persuaded his fellow villagers to embark on some substantial collective endeavors that have transformed his village from an impoverished backwater to a thriving tourist destination: building five kilometers of concrete road down to the main road, establishing a weekly market from scratch, and taking responsibility for clearing litter from the land.

Every Saturday, there is a church meeting in which villagers discuss the best ways to grow cash crops or raise livestock, as well as ensuring discipline in collective tasks being welcoming to tourists. Despite his extensive travels and connections, Ban says all his inspiration came from the Bible.

Pastor Ban (in the suit) with his village congregation. Image by Seb Rumsby.

Even formerly hostile government cadres acknowledge some potentially positive aspects of Hmong Christianity. For example, upon conversion Christians are strongly encouraged to quit drinking alcohol and smoking completely.

Since domestic violence is strongly associated with intoxication, Hmong women see Christianity as a path to empowerment and usually convert first, persuading their husbands to follow them. Although pastors are overwhelmingly men, women comprise the majority of congregations and lead in various activities of the church life.

On the other hand, alcohol consumption is traditionally an important form of male bonding, so refusing to do this has caused conflict between Hmong Christians and non-Christians. Families and communities have been torn apart as both sides harbor bitterness and misunderstanding towards each other, fueled by state denunciations of religious activity.

The qeej instrument (right) is an iconic cultural symbol, but is unpopular among Hmong Christians. Image by Seb Rumsby.

Another concern is that Hmong Christians often reject traditional religious rituals and ceremonies. Even traditional musical instruments like the qeej are treated with suspicion by Christians for their association with traditional funeral ceremonies, and are no longer taught to the next generation.

Many Hmong shamans and non-Christians fear that their culture is being lost. Government officials also worry, because ethnic tourism in the highlands is being promoted by putting these cultures and customs on show. Hmong Christians object to this accusation. Through studying the Hmong Bible, they claim to be preserving their language and script, a crucial aspect of culture that is no longer taught in schools.

In closing, pastors like Ban claim Christianity to be an alternative route to development for the Hmong despite government opposition, but this is contested. These issues are likely to become more and more visible as Christianity continues to grow among the Hmong and the other ethnic groups of Vietnam.

Seb Rumsby is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Warwick.